Bulletin Board

Contact Information

The Max Walker Co.

PO Box 5135 Burnley, Victoria

3121, Australia

Tel: 0417 363 433

Email: admin@maxwalker.com.au

Max Walker

A Max Pac is a composition of information relating to the many aspects of Max's speaking and business fields of expertise. The package includes a CV, testimonials and individual descriptions of the roles Max undertakes.

You can download a PDF version of the 'Max Pac' by clicking the link below:

Download a Max Pac

Looking for something in particular? Try our internal search engine

Sport Spotlights shine on the great shake-up

A game-changing time in Australian sport is remembered.

The Sydney Morning Herald – February 10, 2013 Daniel Lane

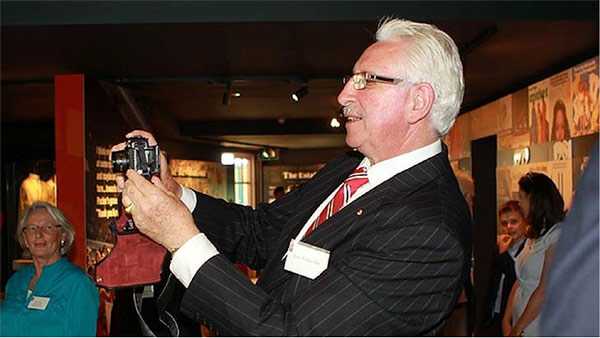

Still in the picture … Max Walker takes a trip down memory lane at the Bradman Foundation lunch

Photo: Sahlan Hayes

MAX WALKER remembers well when the day/night commercialism, colour and rock-concert-like excitement dawned on cricket and he described it as a golden time – in more ways than one.

Walker, one of Kerry Packer’s 54 rebels who left the establishment for a reported $20,000 – a fortune in 1977 – remembers when coloured clothes replaced whites, games were first played under lights, kids wore T-shirts with images of David Hookes and Viv Richards emblazoned on them and stars were paid to endorse products and commercial slogans. There was also the “C’mon Aussie, C’mon” advertisement that became an anthem.

Walker, one of the most popular cricketers of the WSC era, said the commercial aspect appealed to him and allowed him to display his talents via a pesky kid who nagged him about the flies and heat in the old Aeroguard insect spray commercial.

“The kid in that commercial is about 42 now and has his own agency,” said Walker at Thursday’s Bradman Foundation lunch to open the WSC gallery at the Bradman Museum in Bowral. “The commercial was made in 1977 and is referred to as ‘iconic’ now, but it also showcased my potential to be a success on television.”

“I might’ve been the fourth or fifth in line of the talent they could have used, or I might’ve been the cheapest but the right people saw it. WSC was a great stepping stone for a lot of us. You look at the other guys and Hookesy got into radio, Ian Chappell became a commentator and so too Tony Greig.”

The West Indies, who were paid $18 to play a first-class game, couldn’t believe what they were paid by Packer and their fearsome pace bowler Michael Holding revealed through WSC his bankbook had a comma inserted in it for the very first time. However, it came at a price as Walker recalled how he felt to walk on to the hallowed SCG for the first one-day game played under lights in 1979 dressed in the Aussie team’s gold outfit.

“We were in a canary yellow, gold, wattle,” he laughed. “I felt like a Logie the first time I walked out on to the ground. We had flares 28 inches wide so there was a fair bit of a draft coming up the trouser leg.”

Rick McCosker, whose effort to bat in the second innings with his broken jaw swathed in bandages is an enduring memory of the 1977 Australian Centenary Test, remembered the actual cricket as true tests.

“Those two years were tough physically and mentally because we played against the best cricketers in the world every day and there were no easy games,” McCosker recalled. “There was no going back to a club game or a a Shield match because we were banned.”

The early days were a concern as crowds of only a few hundred turned out. Doug Walters, the one-time king of the SCG Hill, remembered how the promise of a massive top up from the gate takings seemed empty.

“Part of our deal was we would get, after Kerry got his money back, whatever millions he’d invested, we’d be on a percentage of the gate two per cent, one-and-a-half or whatever,” Walters said.

There were tough times of a different variety as Dennis Lillee revealed in a documentary. WSC tested friendships and loyalties.

“I remember an incident very clearly when I walked into a supermarket and a guy I played cricket with for some 10-years ducked his head in the aisle as I was going past,” Lillee recalled. “I had to pull him up and say ‘hi’.”

Australian skipper Michael Clarke, who attended the Bradman Foundation’s gathering to honour WSC, wasn’t born when cricket went to war. However, Clarke insisted he appreciated the trappings of success he and his peers enjoy are due to the Ian Chappell-led group of players who had the courage of their convictions.

“We need to be grateful to those people who went before us,” he said. “Without WSC the game wouldn’t be where it is today; the Twenty20 is this generation’s version of WSC. It’s easy to walk into the game of cricket and take things for granted – you fly business class, stay in five-star hotels, make good money but none of that happens without the likes of Kerry Packer and the players who took the risks.

“We’re getting better as a group of respecting our past. The past players coming back into the rooms helps. I think it’s important for the players to come [to the Bradman Museum] and see the gallery and realise how much things changed because of WSC.” For Len Pascoe, a fiery fast-bowler, Clarke’s acknowledgement made the consequences of his decision to count for something more than being just about money.

“It helps when the Australian captain, and someone of Michael Clarke’s calibre, recognises what we did,” Pascoe said. “We’d been vilified during the period as mercenaries and wrecking the game when we actually sacrificed a lot. We sacrificed up to 20 or 30 Tests. Later on in life, when you look at the Tests [record] you don’t see 30, 40 or 50 matches; you don’t take 200 Test wickets. That’s the disappointing aspect.”

However, McCosker put one popular notion about the importance of WSC to rest.

“Cricket would always have survived, even without WSC, it would because it’s a game ingrained in our society,” he said. “The game of cricket always has been, always will be.”